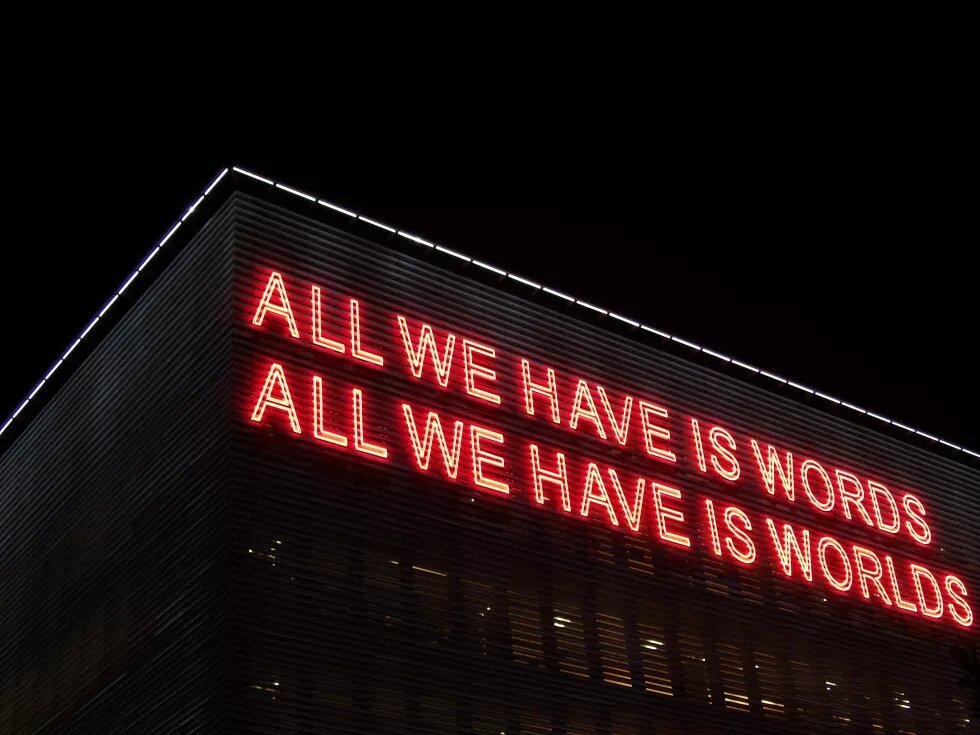

I was introduced to sociology when I was 16. Our teacher used an example from Pierre Bourdieu’s book on social mobility (or lack thereof) in France, quoting the extreme low statistics of factory workers’ children who wouldn’t become factory workers themselves. Having never been trained to think outside the exceptionalism box, I immediately told him that my mom’s father was a factory worker and she’d become a teacher so he could keep his social determinism theory for himself. It took me a couple of classes but in the end I managed to understand what my teacher’s (and Bourdieu’s) point was. Even though they were old white men whose focus was solely on class, they taught me to use social sciences to understand what was happening in my life. Bourdieu did one last thing for me, he’s responsible for a quote that would take all its meaning later in my life: “Words are important”.

When my English level finally got me to the magical Black Feminist theory realm, I discovered thanks to Audre Lorde that if we were to “dismantle our masters’ houses”, we would have to be able to redefine, if not altogether reinvent, our language (amongst other tools). Words are important when you’re in the margins and constantly defined by others, by a history of violence, forced migrations and cultural dispossession. So when someone comes along with a new word and/or a new concept that perfectly encompasses your own experience, that makes that experience intelligible to you when it was hard getting past the weight of the consequences of who you are. When someone brings you the gift of a new understanding of the world and of yourself, you’ll never forget how they made you feel (like Maya Angelou said). This is why writing about “intersectionality” immediately brings back ghosts of scholars and artists who changed my life.

Receiving this new word and concept from Kimberlé Crenshaw was a defining moment in my life such as when “heteronormativity”; “creolization” or “ableism” entered my world. It made me feel powerful, it made me feel like what I experienced was indeed happening and could be addressed in an empowering way. It made me feel the way films by Sembene Ousmane, Dee Rees or Agnès Varda have made me feel. And as a filmmaker who uses the power of cinema to create empathy, awareness and a sense of belonging, I too have been aspiring to create works that would make people—and Black women in particular—feel. What could I do, then? I could create a language of my own, accessible to the widest audience possible. So I decided that my first film would be the film I needed to see when I was a teenager, but didn’t exist yet.

My initial idea was that Speak Up should create a sense of a community through a collection of individual testimonies and make young black women feel less isolated. I wanted them to feel empowered, by hearing and sharing collective tales of discrimination and resilience told by other black women. To tell this story, the narrative arch of the film and the questionnaire it is based on are built on an intersectional canvas—even if the word “intersectionality” is not once spoken in the film. I’ve chosen to make the audience understand intersectionality by witnessing it: listening to 24 black women who address racism, sexism, classism, depression, religion, sexual orientation, maternity and discrimination at work or in school orientation and hearing them speak out about the consequences of these multi-layered discriminations in France and Belgium.

Speak Up has also been a way of addressing an issue that has always bothered me in French scholar and activists’ circles: the idea that anyone can join the struggle, while as a matter of fact most people (especially in black communities) are way too busy just trying to survive and they don’t have the time or the means to organize—or even to acknowledge the scope of what’s affecting their lives. I grew tired of the fact that “intersectionality”, a concept created to account for concrete cases of intersecting discriminations, was not made intelligible for the very people who needed it the most. To me, cinema is the perfect way to remind ourselves that existence is already a form of resistance and that breaking the silence is a subversive act in and of itself. As an indie director I intend to tell, document and preserve the stories and contemporary realities of those who are usually spoken for, or spoken of, while creating my own Afro-diasporic aesthetics.

Time and again cinema has been the birthplace of new languages. To me, filmmaking is a way to reclaim the notion of universality from a black feminist standpoint. Guerilla filmmaking gave me the ultimate creative freedom (and the ultimate ulcers that come with the hassle of self-financing. This freedom allowed me to assert myself through aesthetics: I was free to push the talking heads documentary genre to its limits (with a 2-hour film with no music and extreme close up interviews). I was free to envision documentary filmmaking not only as oral history and archival work but also as an opportunity to create a new visual language. Thanks to Kimberlé Crenshaw, other scholars and artists’ conceptual innovation and language creativity, I was able to gather strength and inspiration to allow myself complete creative freedom.

So, what’s in a word?

A word can be the first step towards emancipation, it can mean endless possibilities to reclaim the narrative and it can inspire others to follow in your footsteps.