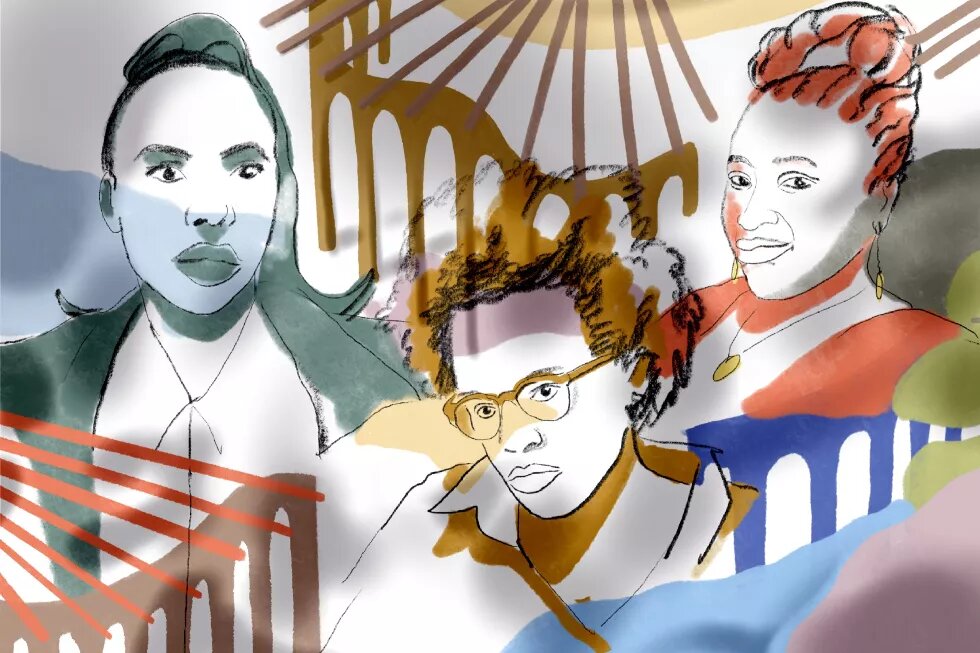

Says writer Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah in a conversation with Dr. Serawit Bekele Debele about African feminist movements and about how the concept of feminism gained traction on the continent.

A talk curated and moderated by Chilufya Nchito. It took place online in October.

Chilufya Nchito: My first question regards anti-feminism from both a historical and a modern-day perspective. How does anti-feminism look today? How did it look in the past?

Serawit Debele: This question is a tricky one, because we are talking about people who were “doing” feminism without actually calling themselves feminists. Can we speak of anti-feminism in a context where people didn’t call themselves feminists? I don’t think so. There has to be an articulation of feminism before we can have the potential for anti-feminism.

For instance, I’m currently working on a project relating to the history of sexuality in the Ethiopian context, looking specifically at the 1990s. Following the end of the military regime in 1991, there was a massive explosion of print media. Most of the published materials were pornographic – but with a liberal agenda, so it seemed like they were part of a sexual revolution. At that time, women got organised, mainly in the cities and particularly in the capital Addis Ababa, and came together in huge demonstrations protesting against the media, which they regarded as disrespectful to women because it objectified them and reduced them to sexual objects. Soon afterwards, most of these publications were stopped by the government. Was this feminist or anti-feminist? I ask this question because of how divided opinions were about the publications. For some, they were regarded as empowering women by encouraging them to own and explore their sexuality. In this sense, it was seen as a component of feminist action that was liberating women from sexual repression. For others, the publications were condemned for reifying the understanding that women are objects of men’s sexual pleasure – meaning there was nothing empowering or feminist about the publications. Here is the dilemma that invites further reflection.

Nana Darkoa: Women getting organised is definitely a feminist act. At the same time, did the women participating in those demonstrations do so of their own free will? That would determine whether it was an instance of feminism or not.

Serawit: If we speak about anti-feminism, I feel there has to be something preceding it to which it is an “anti”. So my understanding of anti-feminism is that it is some form of organised reaction against some form of organised feminist movement in the African context. In saying this, however, I do not want to imply that anti-feminism does not exist; I just mean that it may not call itself that. A quick look at both online and offline spaces shows that anti-feminism is so rampant that it looks like it is indeed a coordinated campaign to attack those who fight for women’s rights.

How is the anti-feminism movement of today? Has it been tainted by a colonial and religious legacy?

Nana: These days, anti-feminism is most strongly expressed in the desire of the state to control women’s bodies, to control the bodies of queer people and of the LGBTQI+ community – to determine who can love, who can have sexual relationships with whom. It’s happening across many African countries. It’s a scary time.

Reclaiming our bodies starts with questioning everything we’ve been told about bodies and what our bodies are for.

Serawit: Absolutely! But it’s not only the state. Popular culture also plays a huge role in promoting anti-feminism. You see that in music videos, talk shows and contemporary religious activities, particularly street preaching, and in the posts of all those YouTubers and TikTokkers who are promoting skewed ideas about womanhood and feminism. We need to ask: How are women being represented, in particular successful, professional, hardworking women? They get harassed; the discussions focus on how they are dressed, their make-up, their hairstyle. They get reduced to their physical appearance. How is their intimate life being spoken about in these posts? There’s massive anxiety around women coming to the fore of political, social and economic spheres in Ethiopia for example, but also in many other places in Africa. There’s a strong pushback against women who are pushing against the limits of patriarchy.

The female body is a site of struggle. Why is it such a contested issue?

Nana: I think it’s because women’s bodies are never seen as belonging to them. They are seen as belonging to their family, and to the state as well. Men seek to control women’s bodies because they want to control women’s reproductive functions; they want to ensure that the children they raise are their children and not the children of other men. States have various agendas when it comes to women’s bodies. Sometimes they want to control them because they’re aiming to control the population, whether they’re seeking to expand or to shrink the population. This plays out in repressive abortion laws and the lack of comprehensive sex education in schools; it plays out in states trying to control who people can love and who people can be in relationships with. That’s why I see the struggle for sexual freedom as a deeply feminist issue. One of the most popular feminist adages is “the personal is political”. Is there anything more personal than owning your body?

Serawit: Women’s bodies became a site of struggle even more after women started saying “No” to that ideology and public attitude. It was normal to simply be in the service of the patriarchy, in the service of the state, in the service of men. There was no “No”. It was when women began to challenge their assigned role and the expectation that they be willing vessels for producing labour in the service of capitalism or sustaining the nation as mothers, as daughters that the debate about what constitutes womanhood and the body started. It’s not a settled question: What is a woman? Under what conditions is a woman allowed to be a woman? What is she excluded from? Where is she included? When does a woman become an improper woman who must be removed or ejected from this notion of womanhood? What are the conditions? Interestingly, we don’t see men struggling to reclaim their bodies in the same way.

It’s interesting how it is so normal for a woman to be invaded. You may be sitting in a particular spot and then a man can simply come up to you and touch you on your thigh or your arm and you are not expected to be offended by that. If you fight, the entire world, in some cases including women, tries to pacify you and talk you into accepting the “common sense” that you seem to have momentarily forgotten. But no woman can ever dare to say: “Oh, you have such beautiful eyes! Can I take you out for a drink?” There would be serious consequences to that, including being ejected from this idea of “respectable womanhood”.

How can we reclaim our bodies as a space for ourselves? How do we fight anti-feminism in our personal lives and as a collective?

Nana: Reclaiming our bodies starts with questioning everything we’ve been told about bodies and what our bodies are for. It’s both a personal and a collective journey.

If there’s anything I learned from writing my book The Sex Lives of African Women, it’s that you need to question what you were told growing up. Reading the work of feminists caused a shift in my thinking. Reading about feminism allowed me to see the contradictions in my own life.

Serawit: Precisely. Also, I think feminism goes beyond reclaiming the body. We need to redefine the feminist question. Because the feminist struggle on the African continent has been almost completely hijacked by a neoliberal/capitalist agenda. We are all about glass-ceiling feminism. We are all about celebrating individual success – which is crucial. But there seems to be marginalisation of the broader historical and structural socio-economic questions. We are mostly trapped by, and content with, representation and visibility. I say this based on some observations. In 2018, there was political change in Ethiopia. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who was highly celebrated and later even got the Nobel Peace Prize, filled the cabinet with 50 percent women. He said he had done that because women are motherly, they are kind, and they are therefore less susceptible to corruption, etc. As feminists, some of us took issue with that idea of presenting women as depoliticised subjects, seeing the potential danger of that viewpoint – and we were seen as ungrateful, if not anti-feminist, because we did not celebrate this problematic representation.

Nana: I think that was not at all feminist.

Serawit: The problem was not that we refused to celebrate their political representation; we wanted to ask more questions. For example, why are women the ones who suffer most from poverty? There are also still massive numbers of infants and mothers dying. We need room to articulate those issues. Ethiopia was at war from 2020 to 2022. Rape was weaponised during that war. So many children, so many women were raped. When challenged, the Prime Minister said: “Why are you talking about rape?” – alluding to the “normalcy” of rape in the context of war. This shows that systemic change is a pressing issue on the feminist agenda. That’s why there is a need to consider how states and neoliberal forces are co-opting feminism. When it comes to the personal, I’m a woman in my 40s, a fairly successful professional, unmarried. Yet everybody wants to know about my personal life. How do I reclaim my body in a situation where I’m reduced to whether I’m married or not, whether I have children or not?

Nana: There have been times when I’ve found myself in intimate situations where I haven’t reacted the way I would have wanted. We must extend grace and kindness to ourselves.

Serawit: Me too. There seems to be a disconnect between our feminist theory and how we think about ourselves.

Nana: Men fail us! Sadly, the reality is that when we’re trying to demonstrate solidarity with Black men, they fail us. The prime minister of Ethiopia you just mentioned is one example of that.

Serawit: Yet fighting anti-feminism can have different perspectives and isn’t always straightforward. For example, while I was reviewing Changing the Subject: Feminist and Queer Politics in Neoliberal India by Srila Roy, a book that focuses on Calcutta, India, I came across a very fascinating example where she shows the tension in feminist practices and the reality of women’s ordinary lives. There is a young girl being given away to a man. Feminist activists in the city had a network of friends and collaborators in that area. So, on the wedding day they went there to say: “This is early marriage, you shouldn’t do it. It’s not consensual.” The bride stood up and said: “I want to marry this man.” Another woman in the village confronted the feminist activists and said: “You’re telling us not to marry her, but what do you have for her? What is prepared for her? Do you have any protection for this woman? Because if she’s not married, she is going to be raped.” I kept asking myself: How do we fight the socio-economic condition that subjects young girls to dropping out of school and forcing them to get married to a man that’s much older than them while also fighting against the ills of such practices?

It’s important to point out the interconnections that feminists have. The world is in chaos right now.

What do we want to pass on to future or younger generations of feminists?

Nana: We shouldn’t overly focus on the anti-feminist axis, though we do need to focus on them to some extent. It’s important to create more spaces for feminist movements, to learn from each other, to share things that are working in other contexts, to support one another, to be together. I think that’s something that doesn’t receive enough support from funders.

Sometimes the reason why there are such rifts in our movement is the lack of adequate space for dialogue, for getting together and seeing where our commonalities are. It’s difficult to make time to meet, to talk, to get to know one another, to build relationships. The issue of solidarity is one that comes up often.

In this particular moment of time, it’s also really important to point out the interconnections that feminists have also highlighted between various struggles. The world is in chaos right now. We have genocides taking place in Sudan, Congo and Palestine for instance, and we see so-called progressive governments acting in really anti-feminist ways by, for instance, expressing “full-scale support” for Israel and being conveniently silent about the need for Palestine to be free and for its people to live on land their ancestors have been on for generations.

It’s also important to call out the hypocrisy in the anti-feminist movement. For example, how they claim that homosexuality is un-African but their own cause is actually being funded by evangelicals from the West. We need to be aware of that. But I would rather focus on feminism itself. Let’s continue to centre on feminist movements.

Serawit: I certainly second everything you say here, Nana. In addition, just like some say homosexuality is un-African, a similar thing is said about feminism being un-African. We need to ask more seriously: How does that affect our practices? Who are these parties saying that feminism is un-African? How does that benefit them? These questions need to be raised in our feminist circles. Once we understand the genealogy of feminism in Africa, we can better position ourselves to defend and promote African feminisms in context. For younger feminists, my advice is to ask yourselves: What do the women around you do? I take a lot of feminism from my mother, from the mothers that raised me. It’s not just from reading Judith Butler. Feminism is not Western in that sense. For me, feminism is what my mother and her friends used to do in raising me and in building a generation that’s aware of their social, political, historical, and cultural environment. I always think about how she would have reacted to the violence perpetrated against women in Ethiopia, Sudan, Congo, Palestine – pretty much everywhere in the world really. I wonder what her imagination and dreams of freedom could have been and what I could have learned from her to make sense of the rampancy of this violence as a feminist ethic and practice.

Thank you all so much! Thank you for the insights you provided and for the work you do.

-----

This talk is part of the dossier Feminist Voices Connected.