Post-feminism and post-race are debates of the past situated in the so-called ‘post-internet’ age. The internet is emerging not only as the focal point of increasing racism but also as a media technology generated by colonial continuities.

The Migros Museum of Contemporary Art in Zurich is currently showing the group exhibition Producing Futures - An Exhibition on Post-Cyber-Feminism. This exhibition was slated in the art and lifestyle magazine Monopol by Anika Meier, who recently curated the show Virtual Normality. Netzkünstlerinnen 2.0 in Leipzig. You’d be forgiven for asking: what’s going on here? Aren’t both exhibitions endeavouring to present positions on ((post )cyber )feminist internet art? In fact, it is these brackets around feminism and cyber-feminism which hint at the crux of the matter. A full understanding of the details requires us to critically re-examine the early relationship between feminism and the internet. After all, cyber-feminism was part of a political discourse about post-feminism. A discussion of post-cyber-feminism today therefore demands that we critically examine an age which considered itself post-feminist. A similar situation can be seen with colonialism. Those like Bill Clinton, who argued in the 1990s that the US were post-race, understand today (as they did then) that this is simply a bad joke. The internet thus contributes to revealing the farce behind claims that racial restrictions have been overcome. In the following paragraphs, I examine not only the racism that plays out on the internet but also the racism of the internet as a media technology generated by continuities of colonialism.

Wired – colonial geographies of the internet

In particular, the rhetoric of wireless communication and decentralised networks has created the impression that digital communication is uncoupled from material conditions and effects. In reality, however, it is the resources, bodies and geographies of marginalised peoples and regions that enable the majority – supported by visual cloud metaphors – to feel there is nothing to worry about. However, as Tabita Rezaire writes in her video essay Deep Down Tidal: the ‘internet is not in the cloud’. The internet is rooted in a colonialism with its own material basis. This concerns both geographic and physical aspects.

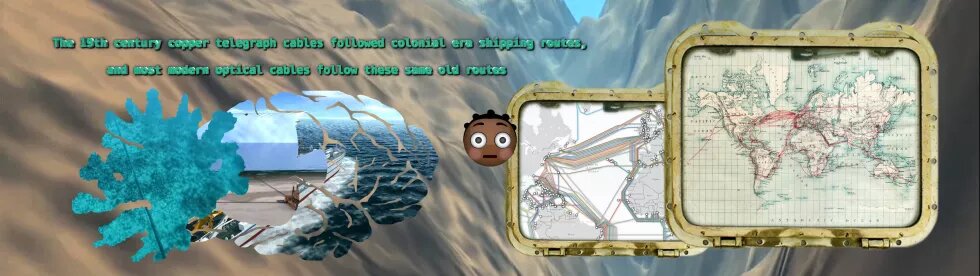

Deep Down Tidal makes the point that even supposedly wireless communication depends upon a network of fibreoptic cables at the bottom of the ocean. These cables follow the route of the old telegraph cables, which in turn followed the routes taken by slave ships. Today’s digital communication follows the mapping of colonial geographies. While the internet is marketed as a sphere of social mobility, it runs along historic and political lines that inscribe inequalities into its DNA. Nicole Starosielski calls this the geographic stasis of the digital environment, arguing that such stasis includes the ‘conservative nature of the cable industry’. Because cable technologies are built to last for at least 25 years, and the old installation techniques continue to be used, the era of territorial colonialism of digital communication is expanding.

Colonialism through geography, as described by Edward Said, also takes place at the end of fibreoptic cables. By laying cables along the shipping routes of early colonialism, the places where cables emerge into view represent regions exploited by colonialism, the effects of which continue today. With regard to the island of O’ahu, one of many cable stations, Starosielski notes: ‘[T]he same beach that makes possible the landing of communication cables (...) is also a temporary dwelling for some of the least mobile Hawaiians’[i]. Limitlessness on the internet is achieved by further immobilisation of people historically affected by colonialism. The same goes for data centres, which the large communication companies build either where there is potential economic benefit or where they can profit from a politically unclear situation that can be traced back to colonialism.[ii]

Mining – the materials of digital colonialism

The myth of the dematerialisation of the internet or the deconstruction of, for example, identity through the internet as suggested by the discourse about post-race, is opposed by the fact that digital experiences are always linked to environments that have hardware as a component, e.g. the tablet that I touch, the chair I sit on, my girlfriend’s picture next to the screen. The myth is also contradicted by the fact that all cable-based data transmission relies not only on the materials that make up the cable but also on the labour required to mine those materials and the energy required to extract them. These three factors – materials, labour and energy – cannot be understood without taking into account the colonial conditions of the global communications industry. When James Bridle writes that the cloud begins with coal [iii], he should not forget to mention that coal mining has been outsourced to regions that are attempting to build economically functioning states under supposedly decolonial conditions. The use of rare elements in the technologies of our digital world will also reinforce the exploitative nature of relationships. Fibreoptic cables, for example, contain germanium, a chemical element found only in low concentrations in very rare sulphide minerals such as argyrodite. Due to the lack of large germanium deposits, it is extracted as a by-product of zinc ore processing. Although the new estimation method by the Helmholtz Institute Freiburg for Resource Technology (HIF), which has been acclaimed by the German Research Foundation (DFG), concludes that commercial demands for germanium can easily be met and that the available amounts are not ‘critical in a geological sense’ [iv], an intensification of mining is inevitable. For this reason, the colonial histories of the ore mines will increasingly come to haunt our technological present. What is worse, regions that have so far been spared any mining and which are often home to indigenous peoples are now moving into the centre of activities. Marisol de la Cadena calls these regions ‘anthropo-not-seen’, i.e. regions so far overlooked by the Anthropocene. By being appropriated against the will of indigenous peoples and against the conventions for ore and oil extraction that guarantee their rights, they become visible to the Anthropocene. This means that the cloud not only has an ecological footprint, but also a colonial footprint, and by no means a small one.

[i] Nicole Starosielski: The Undersea Network, Durham: Duke University Press, 2015: x.

[ii] James Bridle: New Dark Age. Technology and the End of the Future, London: Verso, 2018: 23.

[iii] Bridle: Age, 124, „Digital Power Group, ‘The Cloud Begins With Coal – Big Data, Big Networks, Big Infrastructure, and Big Power’, 2013, tech-pundit.com.

[iv] Annual production of gallium and germanium could be much higher, in: https://www.hzdr.de/db/Cms?pOid=47950&pLang=de&pNid=99, last checked: 11. Februar 2019.